Going to sea requires a bit of humility. If things go wrong, a problem rapidly escalates to absolute catastrophe. Of course, Murphy's Law applies here — anything that can go wrong, will go wrong. Did Murphy describe Poseidon's essential cruelty and get all the credit by having a law named after them? I doubt the old Gods cared about us individually. This means contingency planning is central. My plans tried to reflect the realities of weather, the crew, and the boat.

Since I'm able to write this, you have a hint that things didn't turn into a horror story. This isn't the Tragedy of the Whaleboat Essex or Moby Dick or The Tempest. We did not get hit by falling space junk, either. It wasn't even close.

We have a simple goal: the best possible ocean passage is boring. Really crushingly dull. We want a cycle of staring at the water or the stars for four hours and napping for four hours. CA gets to watch sunrise, I get to watch sunset. That should be all. Distress signals, like flares, are something we want to avoid. And when we encounter a distress signal at sea, we want professionals to sort out the problem while we listen in on the radio.

The passage from Beaufort to Charleston is about 200 nautical miles. While our previous off-shore passages seem to proceed at 6 knots on the average, it feels overly optimistic to count on always being able to do this. What if we have adverse winds or other problems?

One alternative is motoring down the ICW for about a week. It's safe and secure. But. It's a week. And this is peak migration season. Hurricanes are less likely, and everyone else is doing this. The ICW anchorages will be packed.

The offshore passage is 34 hours at 6 knots. This means we need to leave late in the afternoon, sail overnight, all the next day, and one more night to arrive at dawn on the third day. It could be 41 hours if I plan for 5 knots. Planning on a dawn arrival and being late is acceptable. Being late for an evening arrival means finding an anchorage in the dark — no, thank you very much.

How well did I plan this? How well did I analyze the weather forecasts? Will it be one of those bad passages where Poseidon's whims mean exciting things happen? Let's start with getting out of the slip.

Tue9 Morning — New Bern Departure

It's about 6 or so hours from New Bern to Beaufort. The weather was perfect for getting started in an unfamiliar marina — dead calm.

It was cold and we layered up.

In reverse, the Whitby — like most single-screw boats — will pivot counter-clockwise at first. Once she starts moving, she responds to the helm, but the first touch of reverse spins the bow. We've hit a lot of pilings with the bowsprit.

In this particular slip, the pivot counter-clockwise is a big problem.

To get to the river, we need the bow to spin clockwise, to the right. Instead, she starts out counter-clockwise, and we're at risk of getting wedged into a tight mess in the narrow fairway. If the turn to left continues, I'm looking at a concrete wall.

A little forward, with the helm pretty far over will push the bow clockwise. There's a piling there. But — of course — it's not enough to get the bow properly out of the slip. The trick is to pick up 15 degrees of clockwise going forward, and lose half that hitting reverse to keep from banging into the pilings. Or boat next to us. Once we're through about 60 degrees, we can make it. But it's two steps clockwise and one step counterclockwise dance to the music of roaring diesel with shifting gears. (1800 RPM with four cylinders banging away is close to 120 Hz, so, it's in the key of B♭).

It was a squeeze, but, we did it with me saying one thing: "Don't push us away from the starboard side piling." Otherwise, we executed the maneuver really well.

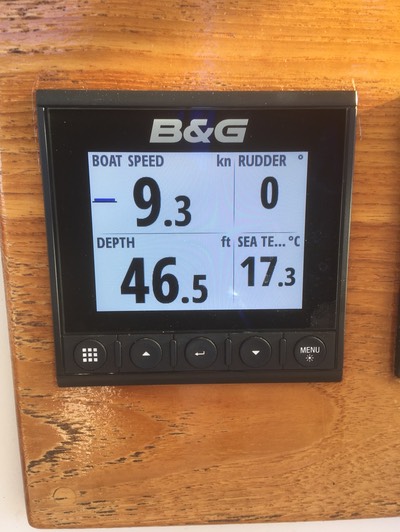

CA took this picture as we were racing down into Beaufort.

Yes, we're doing 9.3 knots. The horizontal line to the left shows acceleration, we're accelerating a little. It's helpful when racing to make sure you're getting through a tack correctly.

The hull can only displace water around it at 7.5 knots. To see this kind of speed means the river is flowing at 3.3 knots; our 6 knots of boat speed looks more impressive.

Which leads to an interesting problem.

What if we arrive early?

I thought I had an airtight plan until I saw this. Now. I have doubts.

If we arrive in Charleston in the pre-dawn hours, what do we do? It's madness to attempt Charleston Harbor after dark. We can't get up the Cooper River to the marina. We've never dropped the anchor after dark. Ugh. This is something we need to plan "on the fly."

Tue9 Afternoon — Exit Beaufort

For offshore passages, I prepare an elaborate "float plan". It has a description of people, boat, and passage. It was the expected check-in times. It starts as a spreadsheet, but I print to PDF and send it to CA's aunt and our kids. They get notification from our SPOT messenger device (www.findmespot.com). This tells them we're doing OK. If we fail to check-in, that's a cause for concern.

The float plan started with leaving Beaufort at 18:00, making 5.7 knots, and arriving at Charleston at 06:00. 5.7 knots.

Exactly.

Slower is okay. Faster leads to an awkward "what now?" situation in the pre-dawn darkness.

This means we left Beaufort entangled with our first problem.

We actually left Beaufort at 16:00 instead of 18:00. We're already two hours ahead of schedule. This means we'll have two hours of — of what? — in the pre-dawn darkness at Charleston. This requires some careful thinking.

There should be plenty of time for that, if nothing else goes wrong.

Tue9 — Dog Watch (16:00 to 20:00, SL)

Was this marvelous weather a setup by cruel Poseidon? Or was my plan going to work? The weather was, as predicted by the Marine Weather Center folks, calm as we could have hoped. The sea was nearly flat. The sky was empty of clouds.

And.

Many, many boats were pouring out of Beaufort. To us, this suggested a lot of other sailors had seen the same weather window and were all on their way south.

CA was peering at other boats, listening to the radio traffic. One boat, Chicory, was on our same track; we hailed them. They were bound for Georgetown, maybe Charleston, they echoed our understanding of the weather.

Two boats were bobbing in the fairway, more-or-less adrift. Each boat had a shirtless guy. One was staring at his phone, as if he needed one more text message before sailing to the Caribbean. Both boats had their sail covers on, as if they hadn't really prepared for going offshore.

For folks — like us — who plan everything and have checklists, this was scary.

For my part of this first watch at sea, I set the autopilot to take us to the Masonboro inlet waypoint. And that was pretty much it.

Mr. Lehman rumbled along at 1600 RPM, and we made the planned 5.7 knots. We had ⅞ tank of fuel — this is about 63 gallons. I'm pretty sure we burn somewhere near 1 gallon per hour at low RPMs like this. (We shouldn't burn fuel at this rate; conventional wisdom says HP÷18 gallons per hour; 1600 RPM delivers 52 HP burning 2.8 gallons per hour.) Can we really count on burning only 48 gallons of fuel? Or should we plan on running through all 72 gallons in 48 hours?

It was so flat and wonderful that CA put together one of their more complex dishes: macaroni and cheese mixed with spinach. Yes, it's boxed mac-n-cheese mix and a ½ box of formerly frozen spinach; it's not fancy gourmet stuff, but it involves mixing and stirring while standing in the galley where you can't easily stare at the horizon to settle your stomach. I count it as a heroic level of cooking. Perhaps hubris. Perhaps a good idea to have a nice hot meal while we can.

Tue9 — First Watch (20:00-00:00; CA)

During their watch, CA found another problem. CA left notes in the log for me to fix it.

A common conversation in the AIWW (often called the ICW, Intracoastal Waterway) is this.

"Red Ranger, Red Ranger, Red Ranger, this is Big Fancy Boat. Over."

"This is Red Ranger on one-six. Over." We know what they want. But. We're polite and wait for them to state their case.

"Can we do a ‘slow pass' on your port side? Over." We expected this; it's standard request #1.

"Copy that: slow pass to port. Over."

And some big fancy cruiser or sport fishing boat goes blasting by throwing a huge wake. About 1 boat in 10 knows how to execute a proper "slow pass"; the rest are simply in a hurry and want us to get out of their way.

(The trick is to wait for the wake to move past us before hitting the gas again. Simply waiting for the stern to get past our bow does nothing. The wake is still coming up behind.)

It's often first-come-first-served at marinas. Important people need fast boats. Waiting around to pass a sailboat isn't part of their day.

CA heard one of these conversations somewhere behind us in the ICW.

"Slow boat, Slow boat, Slow boat, this is Big Important Boat. Over."

"This is Slow boat. Over." There are two paths this conversation can take. Most follow the standard request #1 path. Some, however, are less decisive and ask a bunch of questions.

"What side do you want us to slow pass on? Which side of the channel is better for you? Over."

"Any side. Pick any side! Just get away from me. Over."

CA's problem report noted that the chart plotter's local time offset was still on Eastern Daylight Time. We're now in Eastern Standard Time. The iPhone/Apple Watch had the correct local time. The boat's equipment was off an hour. And, of course, Radio and Chartplotter have separate configurations.

Wed10 — Middle Watch (00:00-04:00; SL)

After fixing the local time offset problem, I got to take the second big step in the plan. Near the Masonboro Inlet, I changed course for Cape Fear. I can try to make it sound important, but it's changing the course from 245° to 205°. There's a knob on the autopilot that does this. And then I settled back to watch the darkness flow by.

Most of my watch is four hours of peering around in the darkness. This is — I think — a good thing. Complacency, of course, is what Poseidon looks for. Complacency born from hubris.

We keep a paper log book. Entries are written each hour, on the hour. It gives you something to look forward to. "45 minutes till log time." "Oooh, only a half an hour till log time." "Yay! 15 minutes till log time." "Ugh. 5 more minutes of waiting to write the log entry." "Yay! logging!"

Then another hour begins.

Wed10 — Morning Watch (04:00-08:00; CA)

The last dregs of the storm system exiting from North Carolina raised some wind and wave action at Cape Fear. I think they were 3′ to 4′ waves, set mostly against us. When Red Ranger hits a big wave speed drops from 5.7 knots to 3.7 knots. It's just ugly.

Our bulwark is almost exactly 4′ above the water, so watching wave tops right outside the cockpit means I've made a terrible mistake in judging the conditions.

And when it's dark and the boat is rolling and bumping, it's doubly nasty.

When you can see the horizon, your various contrary senses of motion are resolved. Your inner ear and eye and core muscles come to a kind of reluctant agreement, and you're not sick. Uncomfortable. But. Not sick.

If you lie down with your eyes closed, sea-sickness is lessened, also. You can isolate eyes, ears, and core. It's hard to lie down when you're on watch. It kind of defeats the purpose of keeping a sharp lookout.

In the dark, when you can't see a horizon, being on watch is as bad as being below decks trying to prepare some food. Or use the head. Or find your flashlight. You're just sick.

CA has some promethazine. It seems to have helped her. This morning watch was not great, but it was better than full-on sea-sickness.

CA is very careful that the space below decks is as quiet as it can possibly be. Yes, there's an 80-horse diesel engine thundering away. But the pots and pans are silent in their storage cupboards. Tools? Silent. Spare parts? Silent. Anything that rattles is swaddled and stuffed somewhere it can't rattle. It makes it easier to sleep when the only noises are water, wind, and engine.

CA took the third big step in the plan. Once past Cape Fear, we set the course to 250°M, bound for Winyah Bay.

Short of Winyah Bay, I don't think there are any good places duck in and hide from weather. Or recover from sea-sickness. Or switch from sailing to motoring down the ICW. The place to make those choices is the Winyah Bay inlet by Georgetown, about 7 hours away.

Did I really read the weather correctly? Is the rest of the trip going to be utterly horrible? Should we have waited for a better weather window?

Wed10 — Forenoon Watch (08:00-Noon; SL)

The wind and sea state settled down. Slowly. Since it was daylight, I could put up sails and try to go faster using less fuel. I'm forbidden from leaving the cockpit alone. Safety officer rules. I can tweak headsails safely. Raising the mizzen, however, would require CA to be up and about. Adjusting the mizzen (for the most part) can be done without anyone else in the cockpit.

Remember how I was worried about arriving early? The contrary wind and waves during CA's morning watch had cut the speed down to 4.4 knots. I felt like I needed to make up for lost time.

This was, it turns out, a serious error. I tried to work out how much more speed when needed. I was staring at the estimated time of arrival (ETA) and TTW (time to waypoint) calculations, trying to figure out what was going on. Before I could figure it out, though, we hit the Rogue Wave.

Waves vary a lot in height. There are waves on top of waves. There's the ocean "swell" with waves riding on top of it, and little wavelets on top of the waves. The wavelets are a local wind phenomenon: below 3 knots of wind, for example, the water appears glassy smooth. There may be waves every few seconds, but they're smooth. And there may be "swell" on the order of 10 to 15 seconds that lifts and lowers the line of waves.

The "wave height" metric that NOAA measures is the average of the highest one-third of all of the wave heights. This corresponds well with our subjective impression of big waves vs. small waves vs. dangerous waves.

Then there's the outlier. The Rogue Wave.

We hit a wave so much bigger than the others that Red Ranger launched off into space. All 21 tons crashed down into the sea, blasting water off to the sides in an impressive pair of bow waves. The bowsprit was buried so far into the water, it bounced one of the anchors loose.

I had been mentally struggling with "ETA of midnight is horrible — slow down" vs. "ETA of midnight at Winyah Bay isn't relevant — speed up" The loose anchor is not helping my sleep-deprived brain reason out the answer to "Are we going too fast?"

Now the Bruce anchor is clanging against something up on the bowsprit. It's 30-odd pounds of galvanized steel, and needs to be tied down so hard it cannot move. Fixing this requires some careful preparation. CA rigs jacklines so we can be clipped to the boat at all times. We wear PFD's with harnesses. We have tethers that clip harness to jackline.

It's polite to hold the tether clips up in the air when moving around on deck. Otherwise, folks sleeping below (i.e., CA) have to listen to the big carabiner dragging down the deck.

Once up on the bowsprit, I will have to rearrange the lines to stop the clanging. Should I bring some extra line? Or are we good with the line that's there?

Turns out, we're good with the available line. Also. It turns out that I can tie knots while riding the roller coaster of a bowsprit.

Generally, the Safety Officer doesn't allow anyone to leave the cockpit without a spotter. However. The rule is intended for heavy lifting tasks like hoisting, dropping, and reefing sails. These tasks require standing on deck, above the lifelines. The bowsprit work can be handled while hunkered down below the lifelines. It's damp, but safe.

Wed10 — Noon Watch (Noon-16:00; CA)

The wind mellowed and then continued to mellow some more. CA wrote "intense crushing boredom" in the log. This is how we know it's a good passage.

CA did not find problems for me to solve. That was also good.

Red Ranger has some established problems. The vent hose on the Nature's Head is falling apart; the aft head smells like coir brick. The fuel return from the engine drips; there's about a pint of diesel fuel trapped in absorbent pads under the engine. We knew about these when we left. (I wring out the pads periodically into a jar of stanky, filthy diesel.)

We have a mystery, also. The bilge pump ran 3 times. We're not sure where — exactly — the water's coming in. We can imagine it's the anchor hawse pipe. But we don't really know.

Wed10 — Dog Watch (16:00-20:00; SL)

After my nap, I can reset my mental computations to focus on Charleston. And throw out my carefully crafted plans.

It turns out, I had been misreading the chartplotter display. Poseidon does that to you. A little fatigue. A little weather. And you can't really think things through clearly.

What I thought: We are in navigation mode. The ETA computation was the end of the route — Charleston Harbor fairway. The TTW computation was to the Winyah Bay waypoint.

What was really happening: We are not in navigation mode; we are just holding a heading to get from place to place. The ETA computation wasn't based on Charleston. It was based on Winyah Bay, 40 miles (and 7 hours) closer to our position than Charleston. An evening arrival at the Winyah Bay mark isn't as bad as an evening arrival in Charleston.

Question. What do we do when we arrive in Charleston at 03:00 AM?

Answer. We drive in circles until sunrise (06:46 AM)

Also, the course change from the Winyah Bay mark to the Charleston mark is about a 1° change in direction. I can change the waypoint to Charleston, discarding the rest of my carefully created plan.

At this point, we're no longer following the elaborate float plan. We're simply looking at the chart plotter and adjust speed and heading any old way that makes sense.

I have plenty of time to think about this and review it from every angle. The wind has collapsed. We are gliding over a flat ocean at low, quiet RPM's. Sailing is fun, technical work. Gliding over flat seas under diesel is a joyous way to make lots of miles. This gives us a ton of time to waste and the most perfect weather for wasting it.

Wed10 — First Watch (20:00-00:00; CA)

At 21:10, Wed 10 Nov, 2021, CA saw a green flare; it was due N of our position. She woke me up. She radioed the Coast Guard. Two other boats in our area reported the flare. There was a big radio confabulation on channel 22A. Boats reporting positions, bearing to the flare, color, all kinds of confirmations that we all saw something.

While we helped sort out a mayday once, this was our first distress signal at night. What do we do? Turn around? And go where? Wait for a distress call?

Our radios have DSC (Digital Selective Calling). This includes a Distress Button on the radio. Push the button and it broadcasts GPS coordinates of your emergency. We've heard the DSC alarm, and we waited for it as we motored through the darkness.

As part of an after-action review, the USCG gave CA a list of questions they need to ask. This is the data you need to gather when you see something:

-

The time

-

Your position

-

The color of the flare

-

Did you see it rising or falling or both?

-

What is the relative bearing to the flare. Use your boat's heading and imagine a clock face with 12 positions. Or. Read the compass if you can.

-

How far above the horizon did it rise? Use your fist, as if you're holding a coffee mug at arm's length and count fists. (Each fist is about 10°.) A flare that's a stack of fists is close. A flare that's barely a fist above the horizon is a long ways away.

Best practice is to write it in the deck log right away, then read it over the radio to the authorities (and other boaters.)

The other witnesses all reported the flare was high. Very high.

Hint. It can't be close to everyone. It has to be higher for some than others. 300m is the typical altitude for a parachute flare. A height of 4½ fists means the flare's peak was 300m away from you. A height of one fist is 1.5 km away. At 3 km from you, the flare will be visible barely ½ fist (two fingers) above the horizon.

About two hours later in CA's watch, the Coast Guard announced that numerous witnesses up and down the US East Coast had seen a piece of Space-X junk burning up on reentry.

Whew. That was a big relief.

And CA didn't like my Charleston waypoint. I had planned to aim for 32°37.23′N, 079°34.55′W. Looking at the AIS reports from other boats around us, she realized they were headed for the red 12 buoy, about 10 nm closer to Charleston. (It's good that the crew can navigate, too. It's a huge weight off my shoulders.)

Thu11 — Middle Watch (00:00-04:00; SL)

After my nap, I have the New Plan. We'll throttle back to almost idle speed. Stretch it out. Avoid circling with other boats and container ships. The sea is flat. Farm pond flat. Pool table flat. Pancake flat.

Venus was so bright it seems like you could read by it. I think I was watching Venus, Saturn, the Moon, and Jupiter all grouped along the ecliptic.

At 02:00 we arrived at red 12 in the Charleston fairway. Since there's nothing more to do, I turned around. At 03:00 we were 6 miles away. At 04:00 we were 7 miles away, idling along over the ocean, watching the stars and the surrounding lights from the boats in the area.

Thu11 — Morning Watch (04:00-08:00; SL)

Yes. I pulled two watches in a row. We're motoring in circles. CA can sleep.

At 06:00 we had our oatmeal and coffee. At 07:00, I turned to motor into Charleston Harbor. There are dredges in the way. There are big ocean-going tug boats. There are container ships, too. The container ships involve a lot of securité announcements on VHF channel 13, so they aren't a surprise. The Charleston Pilots also make sure the pleasure craft are aware of traffic. Because we have AIS tracking, they could hail us by name to give us advice.

At 09:28, we were tied up in slip E2 at the Cooper River Marina.

It was just under 48 hours from New Bern departure to Charleston Arrival. Total distance, including circling and traveling down the Neuse River was 254 miles.

If you count only the hours from New Bern to the arrival in the Charleston Fairway at 02:00, that's about 6 knots. I guess I should use that as a standard speed for Red Ranger.

The fuel gauge reads about ¼. That's ⅝ of the 72 gallon tank. We used about 45 gallons for a 48 hour journey.

Retrospective

What worked?

-

I spent a lot more time on weather details. Years ago, I would look at the NWS zone forecasts, which are terse summaries. MWXC forecasts provides more useful details. Reading the series of forecast emails each day showed how weather evolves at this season and location and what to expect from a weather window. The PredictWind application provides detailed point-by-point forecasts that can be carefully folded into the passage plan.

-

I had a large number of plans, but I didn't have everything. The "What if we go too fast?" plan was not something I worked out in advance. But, I had enough other parts to the plan that we were confident in our ability to make it work.

-

Class B AIS integrated with the chart plotter.

690983B3-F767-499C-ADF1-68D4ED993FDD 1 105 c Check this out.

The solid white triangle in the middle is Red Ranger.

The other while triangles are our posse. These boats are following almost the same course.

The concentric circles are in 5 mile steps. The closest boat is about 3 miles away. Essentially invisible at night. But. Part of our southbound posse.

We knew they were there. Having a peer group like this validated our decision to leave during this weather window. It told us that at least five others reached the same conclusion. Not all pleasure boats have AIS, so there are a few boats that aren't shown on the chartplotter.

-

Prescription anti-nausea.

-

Chartplotter skills. The B&G system was installed in 2017. Between then and now, we've used it for day sails around Chesapeake Bay. CA used the sophisticated wind display and rudder position indicator to help tack more smoothly and consistently. These were game-changing by themselves. But. Now that we can both handle navigation and ETA computations as well as AIS tracking, we're a lot more confident in our ability to manage the complications of a passage.

-

Not getting hit by space junk. It's important to be lucky.

What didn't work?

Can't find anything right now that was a problem. I think the anchor storage needs to be looked at more closely.

What would we do more of?

Watching the weather prior to departure. Getting prescription sea-sickness meds. These really made a huge difference.

What would we do less of?

Not sure, yet. Not too many things went poorly. It felt safe, secure, and boring most of the trip. There were two watches of not boring around Cape Fear, and after that it was — literally — smooth sailing.

Travel

| Attribute | Value |

|---|---|

| Depart | New Bern Dock 35°6.4092′N 77°2.0730′W |

| Arrive | Cooper River Marina 32°46.079′N, 079°52.858′W |

| Distance | 254 nm |

| Time | 48h |

| Engine | 48h |