Competitive Rock Climbing

I shouldn’t be surprised there’s such a thing as competitive rock climbing. As a sailor I know that if there are two sailboats going approximately the same way, it’s a race, pure and simple. Maybe not so cutthroat competitive as America’s Cup or Volvo Ocean Race, but… All it takes is two and it’s a race.

We’ve raced Red Ranger. And lost. Indefatigable beat us bloody when they popped a spinnaker. The yankee is no match for an assymetric spinnaker. Now we want one, too. Joie de Vivre showed us a “clean pair of heels” via better sail trim (and a newer mains’l.)

Competitive sailing — with similar boats on the same water — is obvious. How can you compete in rock climbing?

It turns out that there are three common “disciplines” in this sport. Two that make some sense to me are “sport climbing” and “speed climbing”. The third part of this — “bouldering” — is just magical to me because I can only solve the simplest bouldering problems.

I’ve seen some videos of USA Climbing speed climbing “comps”. It appears that there’s two copies of a standard route and everyone goes head-to-head in that route in pairs. Maybe it’s single elimination, maybe double elimination. I’m vague on the details.

It’s fun to watch. But it’s not a learning opportunity for me. I can’t appreciate the competitor’s decisions because it flits by too quickly. On the other hand, we’ve recently seen sport climbing and it’s pretty cool.

Sport Climbing

In the big national competitions, with announcers and lights and video production, it appears that it’s one climber under the spot light. What we saw last weekend was regional youth competition. It’s not so elaborate as the finals. The gym had stripped the holds from many of the walls to set up at least 30 fresh, new routes. There were also four new Junior routes.

Each route had a number, and a number of points. Points ran from 100 to 2900.

Each competitor has 4 hours on the floor to climb as many as they can.

There’s a taped box around the place your hands must start. There’s another taped box — waaaay up there — where your hands must end. Get from one to the other and you get points.

One wickedly difficult route had no hand hold in the box. You start with your hands flat on the concrete inside the box. Really. People can climb from that starting position.

Fall and you get nothing. In some formats, you can get partial credit for how far you got before you fell. I think that’s reserved for finals and championships where you have judges who can watch and decide if you “controlled” a hold for two seconds before falling.

When we watched the comps, we could see four or five routes very clearly from where we were standing. At the time, we had no clue. A week later, we found that we were looking at a 1000, a 2400, a 2000 and a 1300. Seriously hard stuff.

We now know where the easy ones are. And they’re fun to climb. But not as interesting to watch, since everyone can “send” them — that is — climb to the top. Even me.

Checking the Rules

When I looked at the USA Climbing Rule Book, I saw a table of features a route must have. The points parallel the rating: 5.6 is 600 points; 5.8 is 800 points. The table only went to 1450 — a 5.14d route.

The routes in the gym clearly go to 2900. What does that mean?

To me, it seems like the really tall routes are scored like two shorter routes back-to-back. There’s some standard, it appears, for number of hand-holds and number of moves where your center of mass must go up. Sideways and down moves don’t really count for much.

Often your climb will involve some moves that are merely shifting some hands or feet around without actually going up very far. For example, you move up to a nice big “jug” putting all your weight on your right foot. From there, you can reach up with left foot and left hand to get set for the next move. That placement of hands and feet doesn’t count for much in the scoring because your center of mass didn’t go anywhere. Once you’re set, you can use your left leg to push you up the wall, looking for a new place to put your right foot. This is where the action is — center of mass going upwards.

Last night, I climbed a really tall route worth 800 points. The technical difficulties seemed to be on par with a 400 point route, but it was immense. Twice the height, twice the points, if I understand the scoring — something that’s still doubtful.

A shorter 700 point route was technically far more challenging. It involved two places where the wall leaned out over my head, requiring some tricky hip twisting to get my butt as high as possible while reaching up from under the overhang. And then walking my feet up while hanging from the upper section.

The 100 point route, BTW, was immense but really easy. Even for me. It was like two 50-point routes end-to-end. It’s a good warm-up because it’s long and simple.

Redpointing

The jargon of climbing is a hoot. The point of competitive climbing is to “onsight” the route. From first looking at it, you climb it straight to the top without putting any weight on the belay rope (hangdogging) or touching any holds that are explicitly not on the route (dabbling.)

I was able to onsite the six easiest routes. For #7, I fell. After that first failed attempt, I’ve managed to climb #7 without stopping or falling. That’s called “redpointing”. It’s not as cool as onsighting.

Route #3, however, is a sad story. I “onsighted” it on Sunday after the competition. On Monday, I couldn’t get anywhere with it. Total failure to make the top. My arms were so “pumped” (with lactic acid) that I couldn’t continue the attempt.

Tuesday, I fell again, but CA held me up so I could try again from where I fell. This is called “a take” — taking up the slack in the belay rope. I sent the route “with takes.” Not as cool as redpointing. This #3 route has become my new project route: I need to repoint it again.

Route #8 — 800 points worth — I onsighted. That was encouraging. In principle, it’s a 5.8, close at the limit of my current abilities.

Now that the comps are done, the gym’s route-setters have been putting new non-competitive route on the wall to fill the gym back up with more and more climbing options. Many, many new challenges show up each time we go back.

The James River

After a lot of winter — more than we would have expected for city that’s in “The South” — we were happy to take a good long walk along the James today.

Here’s the link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nghV4SdxgPM. This is what the James River looks like when it’s in Spring flood.

The outing was a quest for the fabled “Manchester Wall.”

Eventually, we succeeded, but the wall deserves a separate video.

Indeed, the wall has its own web page; see Manchester Wall. It has its own Wikipedia entry; see Manchester Wall. The links to the climbing guide are mostly broken. Here’s the current climbing guide.

The Rock Gym

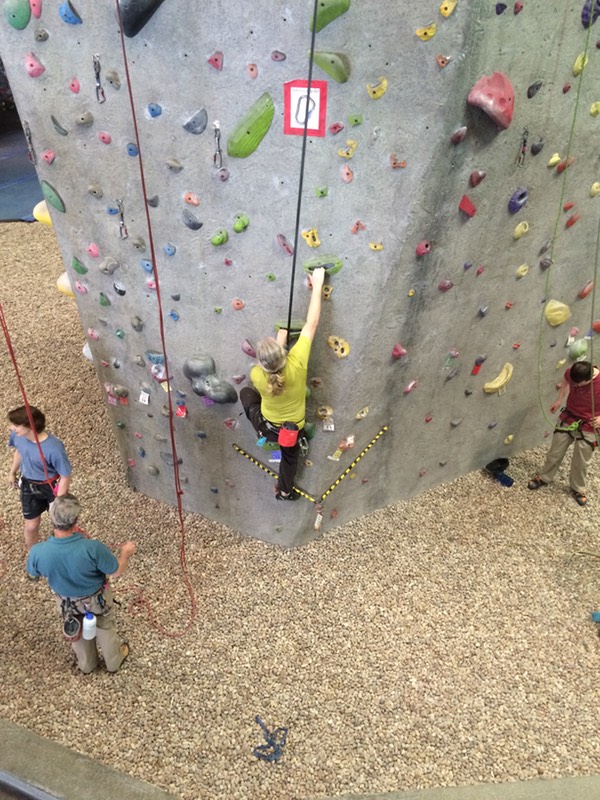

Since it takes two to climb, how did we get these pictures? Glad you asked. Rock climbing is all about puzzle solving. And that’s your little puzzler.

Top rope climbing is a two-player team sport — one person actually does the vertical ascent part — the other person belays them. The climber has a rope (as a sailor, I flinch from the term “rope”) from their harness through a fitting at the top of the route and back down to the belayer on the ground. The belayer, in addition to their harness, has a device to put some friction on the rope. We use ATC-style belay devices — they’re cheap and efficient and have no moving parts to break. As sailors, we like their elegant simplicity.

There’s a little call-and-response that’s a standard part of this kind of technical rock climbing. The climber asks “Belay on?” and the belayer checks everything before announcing “On belay.” Once that’s established, we can move on to the risky part of the transaction. “Climbing?” the climber chants. “Climb on,” the belayer replies and the ascent begins.

Should the climber fall, the belayer uses the ATC friction device to stop them from falling more than a few inches. When the climber reaches the top, the belayer uses the friction device to gently lower the climber back to the ground. Because of the weight difference between climbers, the gym has anchors bolted to the floor. CA uses an anchor sling to make sure she doesn’t get launched into the air if I fall. And I do fall.

The gym has dozens of these top rope routes. There's a big metal bracket at the top of the wall and a 100’ of rope looped over the bracket. The climber and belayer use this pre-rigged top-rope. Traditional (“trad”) climbing uses no fixed ropes. The climber inserts wedges and spikes and other hardware into cracks in the rock. The climber feeds the belay rope through carabiner clips on this hardware. In the event of a fall, they’re going to fall down to the last piece of hardware they inserted. Usually below where they are now. Sounds scary.

Modern “lead” climbing relies on the fact that most places for recreational rock climbing have bolts and tiny stainless steel hangers all over the place. The climber carries a belt of “quick draw” devices that can be clipped into the hangers. The belay rope can be fed through the quickdraw as the climber ascends. It’s like traditional climbing, but it doesn’t rely on natural cracks and crevices.

This gym also has 4 “auto belay” devices. These have a gizmo that winds up your tether as you climb. It’s also a kind of generator (magnets and windings and what-not) that slows your fall to a manageable speed. It’s quite clever and allows one person to climb alone while the other snaps pictures from the balcony.

That’s how we got these pictures today: I’m using the auto-belay.

I think the total vertical on this route is just under 50 feet. There’s a red-bordered sign with a picture of a carabiner clip part way up to remind you that you should have clipped in before you started; continuing to climb without a belay is going to prove dangerous if not fatal. After all, there’s no call and response with the auto belay device. No one reminded you to clip in.

The red bag that I’m wearing holds powdered chalk. When your hands get sweaty, the chalk dries the sweat and also helps give you more friction on the hand-holds. The shoes are Evolv rock climbing shows. A narrow, rubbery sole and really unpleasant for anything other than climbing. Many folks wear flip-flops around the gym and only put the shoes on at the last second before they climb.

And yes, the wall is a bewildering array of handholds. They are, however, color coded. I’m on a green route, named “Wonder Twins Activate” (I have no idea; don’t ask me what it means.) The challenge is to find your way up using only the Wonder Twins Activate green holds. Ignore all of the others. The same auto belay has two other routes in different colors: "The Squeeze" uses orange holds and “Lift It, Drop It, Shake It, Pocket” uses yellow holds. The orange holds aren’t too photogenic. But the yellow holds are easy to see.

Some hand-holds are designed to mimic real rock. Others seem like they're designed just for indoor gym use. And others are just funny. The Wonder Twins Activate route has three handholds that are doll heads. Not empty plastic Barbie heads. They’re substantial chunks of plastic. With little faces. Ears and all. Very strange. But relatively easy to grab onto, once you get over the little face.

Climbing routes have a difficulty rating. 1 is anything you don’t need to use your hands. From flat to steep stairs. 2 is a hill so steep you have to use your hands to scramble up; think ladders. 3 is rocks that require hands, but there are few big voids — a fall might hurt but would not be dangerous. 4 requires hands, and involves voids where a fall is dangerous. 5 means that technical gear is absolutely required for safety.

Once you get to the 5 threshold, they subdivide the difficulty. 5.1 though 5.5 are relatively easy. They won’t involve tricky techniques. You just need to be belayed because the fall is long or involves overhangs. Teetering along a narrow ledge on a cliff could be a 5.1 because it requires a belay, but isn’t a difficult climb. At the gym, the routes 5.5 and below are called “party routes” because the staff take the birthday parties and scout troops to those routes. When you go for your one-day intro to climbing, you do party routes.

5.6 through 5.9 is where it gets more serious. The original plan was to divide all of climbing into the decimal scale. 5.9 was (originally) the most difficult thing a person could possibly climb.

But then equipment and skills raised the bar. Routes now go well past 5.13. 5.10 is hard and 5.13 is seriously crazy. It involves stretches, contortions, super-human strength and endurance.

When we started climbing, we did party routes. After a few days we braved the 5.6’s. There’s a route called “Orange Me Not” which defeated me several times before I got past the hard part — the “crux” — part way up the wall. My first four or five attempts involved me falling off the wall and CA catching me on belay. Eventually, I figured out how to get past this one place where my feet were out of position so badly I couldn’t seem to go anywhere. One of the other climbers calls this “the sequencing problem.” You play the wall like a hand of cards. “I do right hand up… but where do I put my left? Okay, I’ll do left hand up, then right, but then where do I move my feet? Who’s holding the Jack of Trump? Oh, wait, that’s one of my orange holds over there. Okay. I’ll do right hand up, left hand over to that, then I can put my right foot there… Oh botheration, that will never work because I’m not 7’ tall!”

We can do most of the 5.7’s in the gym without too much trouble. A few are very hard and I can’t do them when I’m too tired. CA and I can sometimes get up the 5.8’s. It’s a struggle. One particular 5.8 route — “Climbing Arête” —has defeated us both. We’ve gotten to a spot where we have no clue what we should do to get further up. We know there’s a trick to it. We think it involves reaching around the corner (the “arête.”)

We think we need to see someone more experienced do the route. However. Getting advice like that (the rock climbers call it “beta”) is frowned upon. Most climbers prefer to solve the route on their own. Each route is a puzzle. So we’re going to keep trying different things on this route. We have a new theory after I fell today. Monday night, we’ll try a different approach to that puzzle. "Climb it enough, you’ll find a solution,” we were told. And that seems to be true.

Richmond Sights

It appears that they do this on purpose: they shoot under the railroad bridge, then — somehow — raise the bow up and drop their heads into the water before hitting the next waterfall.

The railroad bridge is after some flat water in the middle of the sequence of rapids.

I know that the upper section is the “Hollywood” rapids. I’m sure the kayakers have names for every feature. I’ve seen some charts with circles and arrows and labels.

Here’s the view upstream from the railroad bridge. You can almost see the Hollywood rapids in the top of the picture, near Belle Island.

As a sailor, I’m more comfortable looking at that stretch of water. I’ve seen things like that in the ICW. It has no Aids To Navigation (ATONs) so it’s obviously dangerous. But it’s flat. All one color.

Here’s the view downstream.

Yikes.

It had been raining for several days, so the water level is up a little. You can’t see the rocks.

We’re looking forward to spring floods to see how the river changes. We’re not looking forward to next year’s hurricane season. In the past the 14th street Mayo bridge has been under water.

Yes. Bridge under water.

I don’t know if seeing rocks is good for kayakers or bad. Seeing them might help maneuver. On the other hand, if you see them, then the water won’t sweep you past them. Maybe next spring we’ll take some kayaking classes.

I think this location is six or maybe eight blocks from our apartment. It’s not the same as a water view out the cockpit. But it will do for now.

Have a Happy and Prosperous New Year.

Closing the Circle

A few years ago, one of the bigger boat jobs was adding a second electric bilge pump. See A Manifold of Bilge Pumps. At the time, it felt epic because it was a job that was safety-critical. As in “your life depends on doing this right.” Or maybe “Do this wrong and die.”

We’ve read enough to know what happens when a boat has an unstoppable hull-breach. Water over the floorboards. Batteries flooded. No radio. No lights.

We had tackled a few safety critical jobs before this. The sink drain hose, for example. Rebuilding the seacocks. But those are big, static, heavy-duty pieces of hose and bronze. The seacock could be closed to keep water out, and that was that. Simple. Done.

Not so with an electric pump.

The Worrying Budget

The bilge pump involved much more worry than the seacocks. In some ways, it also involved less worry.

More worry came from many sources, starting with its electical side — is it hooked up right? I decided to wire it permanently to the house batteries, with only a small fuse. (Eventually this became two fuses, a main 200A fuse to protect the big wires, and the little 10A fuse to protect the pump.)

The pump is plumbing. Can it lift water all the way from the deep bilge to the exhaust port?

Plus, there’s the “manifold” question: is it really sensible to have so many hoses terminating near each other? What about water flowing in a circle and running back down to the bilge? (Eventually, I replaced the manifold with separate through-hulls.)

Plus, there’s the working upside down over the deep bilge to install the damn thing. Every tool and part dropped was over 4′ away and sitting in grungy bilgewater. That slows progress down.

Balancing these worries was the fact that it’s just a backup. We have two other bilge pumps.

Or so we thought.

(We’ve since raised the number of pumps to a total of four, but that’s another story.)

The Whale Gusher 10 Mk II manual pump is elegant, over-engineered simplicity. A giant rubber diapragm and two one-way flapper valves. All fit into a giant aluminum block with huge stainless screws.

It might have worked. Or it might not have. It’s hard to test, since we had a relatively dry bilge. I suppose we could have used a hose to fill the bilge with dock water and test it. But. It’s so simple, what could go wrong?

With two electric pumps, it doesn’t matter, does it?

Are those famous last words?

Rainwater

Last weekend, we visited Red Ranger to exchange tools, look at the sail covers, and generally assure ourselves that everything was fine.

I noticed that our surveyor had carefully turned off every single circuit breaker. That includes the breaker for the lower of the two electric bilge pumps. I reset the panel and the pump #1 kicked on.

No big deal. Right? A little rain. A little condensation. Of course there’s water in the bilge.

But it ran. And ran. And ran. And continued running. I could hear the water coming out. It wasn’t a damaged float switch.

So I pulled up some floor to look in the deep bilge. The water was up to the second — higher — float switch. This is the switch for the “#2” pump I put in back in 2010. The pump that’s wired to be always on. The pump that must have been working to keep the rainwater out! The lower pump was switched off, so this was the only working pump.

And my worry-filled installation had — it turns out — been worth it. The #2 pump had properly acted as the failover. Just like it was designed to. Back in 2010 before we knew much about Red Ranger.

Test Time

And Hey! The bilge is full of water! This is a chance to test the manual pump!

I grabbed the lever and pumped. And pumped. And pumped. And pumped.

The manual pump was doing nothing. Zero. Zilch.

I took the hose off and had CA pump air to see if it was generating any suck at all.

The answer? No Suck. None.

At least the electric pumps still work.

The #1 pump (which had been switched off) has the lowest float switch. It would have worked. It also has a digital counter so we know how many times it has run. The #2 pump has a low intake, but a higher float switch. It’s strictly fall-back. And it worked!

The super-simple manual pump?

The rubber bits appear to be shot.

Rebuild kit is on order.

The Rainwater

The water? We get some water in through the hawsepipe. Also, we get water down the mast. But normally, that’s hardly noticeable.

CA thinks that leaving the head portlights open for ventilation was the mistake. That’s what let many gallons of rainwater into the bilge. We’ve closed the ports.

Merry Christmas from Red Ranger

It’s still early, but, we aren’t doing much on Red Ranger this season. We’re parked on the hard in Deltaville.

Working life is interesting. That was the point, more-or-less.

What’s very important is the “I don’t have any career aspirations” part of working. If it’s fun, that’s cool. Otherwise… No thanks.

In my previous incarnation (pre-cruising,) I would listen to managers spin yarns of advancement and riches and glory. It could all be mine if I would just put in lots more hours and lots of travel and do things that I found difficult and unpleasant.

And it never worked out well. It was stressful, and unpleasant, and there were neither riches nor glory. For me. The managers didn’t do too badly. I didn’t do as well.

After many years of thrift and economy — and more than our fair share of luck — we’re able to make choices in where and how we work. Floating Leaf makes her Tiny Quilts. They’re hanging in the Urban Farmhouse coffee shop in Scott’s Addition at 3031 Norfolk St. She also works part-time at VCU; she does what she like — helping people solve technology problems. Since it’s part time, stuff just won’t get done. She’s no longer salaried; there’s no casual overtime.

I’m working; but taking it easy. I feel the need to excel. Deadlines loom. Stuff isn’t getting done. But.

But.

It’s not like we’ve got a hole in a fuel line that’s spraying diesel down the side of the engine block. It’s not like we’ve got a leaking stern tube and water’s spraying in around the prop shaft. It’s not like we’re pounding into 5’ seas in the Cape Fear river. It’s not like we’ve wrapped a crab pot line around the prop shaft. Nothing like that. We’re not low on fresh water. There’s no crud in our fuel. Our heat exchanges aren’t dripping. Our chart plotter isn’t blanking out.

Nope. This second career isn’t quite like the first. Our two-year cruise helped put life into perspective.

Merry Christmas.

Things you can’t store on a boat

#1: Leather.

It mildews rapidly unless you’re airing it out constantly.

Here are CA’s gloves that we wore last winter as we worked the boat south.

These were bagged to prevent them from getting wet in their storage locker.

Whatever spores were in there loved the dark confines.

Many of the clothes are in our apartment now. The rest should probably be laundered as part of winter layup.

I think all of the shoes and boots are off the boat. We kept some nice-looking shoes aboard in case we had weddings for funerals to attend. They didn’t fare so well. They were rarely worn, and suffered from some mildew. They were shoes, though, so hard cleansers work out fine.

The paper books are bagged. But I’m starting to think that they may all benefit from some airing out while Red Ranger sits on the hard.

Plus, there are some tools that might be helped by some oily wipe-down.

GPSNavX and Yosemite

Upgraded the laptop to Mac OS 10.10, Yosemite.

This leads to many software upgrades.

It leads to GPSNavX not working at all.

Sigh. The Involuntary Upgrade. Unpleasant, but necessary.

I went to the App Store and plunked down my $59.99 for the latest and greatest version.

I open the new version and…

NO WAYPOINTS!

NO TRACKS!

NO ROUTES!

ALL GONE!

Remain calm. Breathe.

I am a professional.

But...

EVERYTHING’S GONE!

Stop shouting. It will be okay.

The Commodore asks her calming, soothing question:

“What was the last thing you changed?”

THE SOFTWARE!

“Stop shouting,” she says.

Okay. She’s right. Stop shouting.

I went to the documentation and found that the files reside in a hidden folder: my ~/home/Library/Preferences folder. A folder I didn’t know existed.

The five relevant files are in there, with dates in the past and sizes that indicate that all is not lost.

What to do?

Well…

I can hack around. Or I can remain calm and email the tech support folks.

The answer came within minutes.

Let me emphasize that. Within minutes they responded with a simple copy the files to a new location.

From the old ~/home/Library/Preferences folder, where they remain untouched to the new ~/home/Library/Application Support/GPSNavX folder.

That was it. Nothing much to it.

And they responded to the email within minutes.

None of this “Here’s your tracking number, someone will get back to you within 24 hours.”

Within minutes. My tracks, routes and waypoints are all back in place.

For only $59.99.

Winterizing

Sigh.

The fun thing (two weeks ago) was ascending the mast to examine someone else's lighting. They had a short. Somewhere. I want aloft to look around. It didn’t seem to be up there. The Aqua Signal was clean and tidy. Bulbs looked good.

Sadly, they’d looked at the wiring at the base of the mast. On a Whitby, it’s a connector block in the forward head. Wiring was good up to the block. And it looked good at the top of the mast.

That leaves just the 56’ of wire going up the mast as the likely cuplrit. They decided that perhaps they could continue hanging and all-around white light from their mizzen rather than use the mast-head all-around white light.

The rules are clear: “where it can best be seen.” Masthead clearly meets “best”. Any white light above the dodger would also be visible all around the vessel and would constitute a workable “best”.

Some folks don’t like using the masthead light because power boaters aren’t in the habit of looking up.

I couldn’t solve — or even properly diagnose — their problem. But I got to play aloft. That was fun.

Real Work

On Red Ranger, we did some real work.

That’s us getting hauled out for the winter. Bottom paint looks good. Some slime, some barnacles, but generally intact.

The zinc was gone. Again. The last time I looked was in February or March in Florida. No zinc. It barely lasts 6 months. I’ve got to rig an additional zinc that I can use in the slip and at anchor. The prop shaft zinc is going way too quickly.

Martyr makes a big grouper-shaped anode with a big old electrical clip. I know some folks who have one clipped to a bonded part of the rigging. I think I can use a small 30A female to 15A male pigtail in the AC socket to expose the AC ground — which I think is bonded to the rest of the boat, and should provide a handy place to clip the zinc fish when at anchor or at a dock.

The Downgrade

Have we mentioned this yet? We’ve been downgraded from cruisers to weekenders.

And that means hauling out and winterizing.

No Florida for us. No Bahamas, either.

Here’s CA putting the famous “pink stuff” into the cooling system.

The previous owner had a 5-gallon drywall pail with a ¾” garden hose fitting punched through the bottom. Drippy, but acceptable for this job.

Red Ranger's sea chest has connections that provide raw water for engine cooling, head flushing and the sink. This also has a matching ¾” hose fitting.

Very nice.

Raw water from the sea chest can also be used for refrigeration and air conditioning. Both of those have been removed from Red Ranger. We left the aft head and fridge hoses capped but still connected. The old A/C hose is connected to the galley sink.

CA connects the magic bucket to the raw water input. She pours in 6 gallons of West Marine Pure Oceans Antifreeze. (30% Propylene Glycol.) I start the engine and let it run for somewhere between 30 sec. and 1 minute.

Once pink stuff is blowing out the exhaust, the raw water system is filled with antifreeze. We can pump what’s left in the bucket through the galley sink and head. Raw water replaced with Propylene Glycol water that won’t freeze.

Then we turn on the freshwater system and let it run until it’s pumping air. That assures that the freshwater plumbing won’t freeze and crack, either.

The 5 gallon gocery store drinking water jug is left in the sink. If it does freeze, it’s not going anywhere. The distilled water used to top up the batteries is left in the forward head sink. Same contingency. If it freezes and cracks the jug… So what? I drains into the parking lot under Red Ranger.

The cushions are turned up on end to let air circulate.

Here’s a typical checklist: http://www.boatus.com/seaworthy/winter/winterworksheet.pdf. We could stand to be a bit more scrupulous on draining the hot water heater. January and February do have nights below freezing. If we’re only going to weekend, I do need to change the oil before winter layup, since we’re unlikely to hit the 200 hour mark in a given year.

If we can sail even 20 weekends (ha!) that would be 10 hours of motoring each weekend before normal engine service intervals were reached. Realistically, we might get in 10 weekends; 20 hours of motoring? Doubtful. Need to start changing the oil based on the calendar, not on the engine hours.

Next spring?

Paint the bottom. Polish the stainless steel wheel. Look at redoing the cockpit benches with new teak caulking. Rig a zinc fish.

Southbound Farewells

In Deltaville this weekend, we visited with boats heading south: Bellatrix, Joie de Vivre, Island Time and Rovinkind II.

All heading south.

All except Red Ranger.

We’ll be traveling with them vicariously.

Joie de Vivre will be heading offshore to make St. Augustine in one big outside run. The weather starting on Sunday looks favorable for them to try that.

Bellatrix will be picking their way down the ICW starting Sunday. If you want to know more, check out the October 2014 edition of Spinsheet Magazine. Page 84 to 86.

Rovinkind II is going to make some repairs before heading south. Island Time is almost ready to head south after considerable work getting everything shipshape after sitting on the hard for a few years.

Red Ranger is getting cleaned up prior to haulout.